“Judgement is what analysts use to fill gaps in their knowledge. It entails going beyond the available information and is the principal means of coping with uncertainty. It always involves an analytical leap, from the known into the uncertain.”

– Chapter 4, Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, Richards J. Heuer.

Analytical leaps, as Richards J. Heuer said in his must-read book Psychology of Intelligence Analysis, are part of the process for analysts. Sometimes though these analytical leaps can be dangerous, especially when they are biased, misinformed, presented in a misleading way, or otherwise just not made using sound analytical processes. Analytical leaps should be backed by evidence or at a minimum should include evidence leading up to the analytical leap. Unfortunately, as multiple analytical leaps are made in series it can lead to entirely wrong conclusions and wild speculation. There have been three interesting stories relating to industrial attacks this December as we try to close out 2016 that are worth exploring in this topic. It is my hope that looking at these three cases will help everyone be a bit more critical of information before alarmism sets in.

The three cases that will be explored are:

- IBM Managed Services’ claim of “Attacks Targeting Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Up 110%”

- CyberX’s claim that “New Killdisk Malware Brings Ransomware Into Industrial Domain”

- The Washington Post’s claim that “Russian Operation Hacked a Vermont Utility, Showing Risk to U.S. Electrical Grid Security, officials say”

“Attacks Targeting Industrial Control Systems (ICS) Up 110%”

I’m always skeptical of metrics that have no immediately present quantification. As an example, the IBM Managed Security Services posted an article stating that “attacks targeting industrial control systems increased over 110 percent in 2016 over last year’s numbers as of Nov. 30.” But there is no data in the article to quantify what that means. Is 110% increase an increase from 10 attacks to 21 attacks? Or is it 100 attacks increased to 210 attacks?

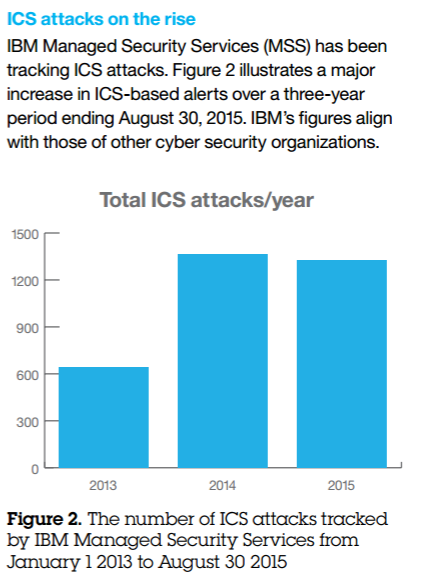

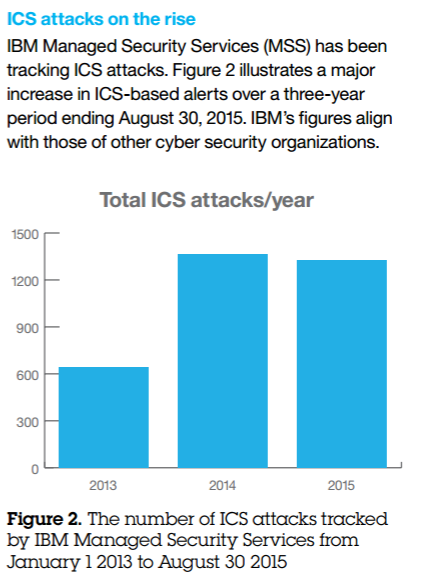

The only way to understand what that percentage means is to leave this report and go download the IBM report from last year and read through it (never make your reader jump through extra hoops to get information that is your headline). In their 2015 report IBM states that there were around 1,300 attacks in 2015 (Figure 1). This would mean that in 2016 IBM is reporting they saw around 2,700 ICS attacks.

Figure 1: Figure from IBM’s 2015 Report on ICS Attacks

However, there are a few questions that linger. First, this is a considerable jump from what they were tracking previously and from their 2014 metrics. IBM states that the “spike in ICS traffic was related to SCADA brute-force attacks, which use automation to guess default or weak passwords.” This is an analytical leap that they make based on what they’ve observed. But, it would be nice to know if anything else has changed as well. Did they bring up more sensors, have more customers, increase staffing, etc. as the stated reason for the increase would not alone be responsible.

Second, how is IBM defining an attack. Attacks in industrial contexts have very specific meaning – an attempt to brute-force a password simply wouldn’t qualify. They also note that a pentesting tool on GitHub was released in Jan 2016 that could be used against the ICS protocol Modbus. IBM states that the increase in metrics was likely related to this tools’ release. It’s speculation though as they do not give any evidence to support their claim. However, it leads to my next point.

Third, is this customer data or is this honeypot data? If it’s customer data is it from the ICS or simply the business networks of industrial companies? And if it’s honeypot data it would be good to separate that data out as it’s often been abused to misreport “SCADA attack” metrics. From looking at the discussion of brute-force logins and a pentesting tool for a serial protocol released on GitHub, my speculation is that this is referring mostly to honeypot data. Honeypots can be useful but must be used in specific ways when discussing industrial environments and should not be lumped into “attack” data from customer networks.

The article also makes another analytical leap when it states “The U.S. was also the largest target of ICS-based attacks in 2016, primarily because, once again, it has a larger ICS presence than any other country at this time.” The leap does not seem informed by anything other than the hypothesis that the US has more ICS. Also, again there is no quantification. As an example, where is this claim coming from, how much larger is the ICS presence than other countries, and are the quantity of attacks proportional to the US ICS footprint when compared to other nations’ quantity of industrial systems? I would again speculate that what they are observing has far more to do with where they are collecting data (how many sensors do they have in the US compared to China as an example).

In closing out the article IBM cites three “notable recent ICS attacks.” The three case studies chosen were the SFG malware that targeted an energy company, the New York dam, and the Ukrainian power outage. While the Ukrainian power outage is good to highlight (although they don’t actually highlight the ICS portion of the attack), the other two cases are poor choices. As an example, the SFG malware targeting an energy company is something that was already debunked publicly and would have been easy to find prior to creating this article. The New York dam was also something that was largely hyped by media and was publicly downplayed as well. More worrisome is that the way IBM framed the New York dam “attack” is incorrect. They state: “attackers compromised the dam’s command and control system in 2013 using a cellular modem.” Except, it wasn’t the dam’s command and control system it was a single read-only human machine interface (HMI) watching the water level of the dam. The dam had a manual control system (i.e. you had to crank it to open it).

Or more simply put: the IBM team is likely doing great work and likely has people who understand ICS…you just wouldn’t get that impression from reading this article. The information is largely inaccurate, there is no quantification to their numbers, and their analytical leaps are unsupported with some obvious lingering questions as to the source of the data.

“New Killdisk Malware Brings Ransomware Into Industrial Domain”

CyberX released a blog noting that they have “uncovered new evidence that the KillDisk disk-wiping malware previously used in the cyberattacks against the Ukrainian power grid has now evolved into ransomware.” This is a cool find by the CyberX team but they don’t release digital hashes or any technical details that could be used to help validate the find. However, the find isn’t actually new (I’m a bit confused as to why CyberX states they uncovered this new evidence when they cite in their blog an ESET article with the same discovery from weeks earlier. I imagine they found an additional strain but they don’t clarify that). ESET had disclosed the new variant of KillDisk being used by a group they are calling the TeleBots gang and noted they found it being used against financial networks in Ukraine. So, where’s the industrial link? Well, there is none.

CyberX’s blog never details how they are making the analytical leap from “KillDisk now has a ransomware functionality” to “and it’s targeting industrial sites.” Instead, it appears the entire basis for their hypothesis is that Sandworm previously used KillDisk in the Ukraine ICS attack in 2015. While this is true, the Sandworm team has never just targeted one industry. iSight and others have long reported that the Sandworm team has targeted telecoms, financial networks, NATO sites, military personnel, and other non-industrial related targets. But it’s also not known for sure that this is still the Sandworm team. The CyberX blog does not state how they are linking Sandworm’s attacks on Ukraine to the TeleBots usage of ransomware. Instead they just cite ESET’s assessment that the teams are linked. But ESET even stated they aren’t sure and it’s just an assessment based off of observed similarities.

Or more simply put: CyberX put out a blog saying they uncovered new evidence that KillDisk had evolved into ransomware although they cite ESET’s discovery of this new evidence from weeks prior with no other evidence presented. They then make the claim that the TeleBots gang, the one using the ransomware, evolved from Sandworm but they offer no evidence and instead again just cite ESET’s assessment. They offer absolutely no evidence that this ransomware Killdisk variant has targeted any industrial sites. The logic seems to be “Sandworm did Ukraine, KillDisk was in Ukraine, Sandworm is TeleBots gang, TeleBots modified Killdisk to be ransomware, therefore they are going to target industrial sites.” When doing analysis always be aware of Occam’s razor and do not make too many assumptions to try to force a hypothesis to be true. There could be evidence of ransomware targeting industrial sites, it does make sense that they would eventually. But no evidence is offered in this article and both the title and thesis of the blog are completely unfounded as presented.

“Russian Operation Hacked a Vermont Utility, Showing Risk to U.S. Electrical Grid Security, officials say”

This story is more interesting than the others but too early to really know much. The only thing known at this point is that the media is already overreacting. The Washington Post put out an article on a Vermont utility getting hacked by a Russian operation with calls from the Vermont Governor condemning Vladimir Putin for attempting to hack the grid. Eric Geller pointed out that the first headline the Post ran with was “Russian hackers penetrated U.S. electricity grid through utility in Vermont, officials say” but they changed to “Russian operation hacked a Vermont utility, showing risk to U.S. electrical grid, officials say.” We don’t know exactly why it was changed but it may have been due to the Post overreacting when they heard the Vermont utility found malware on a laptop and simply assumed it was related to the electric grid. Except, as the Vermont (Burlington) utility pointed out the laptop was not connected to the organization’s grid systems.

Electric and other industrial facilities have plenty of business and corporate network systems that are often not connected to the ICS network at all. It’s not good for them to get infected, and they aren’t always disconnected, but it’s not worth alarming anyone over without additional evidence. However, the bigger analytical leap being made is that this is related to Russian operations.

The utility notes that they took the DHS/FBI GRIZZLY STEPPE report indicators and found a piece of malware on the laptop. We do not know yet if this is a false positive but even if it is not there is no evidence yet to say that this has anything to do with Russia. As I pointed out in a previous blog, the GRIZZLY STEPPE report is riddled with errors and the indicators put out were very non-descriptive data points. The one YARA rule they put out, which the utility may have used, was related to a piece of malware that is publicly downloadable meaning anyone could use it. Unfortunately, after the story ran with its hyped-up headlines Senator Patrick Leahy released a statement condemning the “attempt to penetrate the electric grid” as a state-sponsored hack by Russia. As Dimitri Alperovitch, CTO of CrowdStrike who responded to the Russian hack of the DNC, pointed out “No one should be making attribution conclusions purely from the indicators in the USCERT report. It was all a jumbled mess.”

Or more simply put: a Vermont utility acted appropriately and ran indicators of compromise from the GRIZZLY STEPPE report as the DHS/FBI instructed the community to do. This led to them finding a match to the indicator on a laptop separated from the grid systems but it’s not yet been confirmed that malware was present. The Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin then publicly chastised Vladimir Putin and Russia for trying to hack the electric grid. U.S. officials then inappropriately gave additional information and commentary to the Washington Post about an ongoing investigation which lead them to run with the headline that the this was a Russian operation. After all, the indicators supposedly were related to Russia because the DHS and FBI said so – and supposedly that’s good enough. Unfortunately, this also led a U.S. Senator to come out and condemn Russia for state-sponsored hacking of the utility.

Closing Thoughts

There are absolutely threats to industrial environments including ICS/SCADA networks. It does make sense that ICS breaches and attacks would be on the rise especially as these systems become more interconnected. It also makes perfect sense that ransomware will be used in industrial environments just like any other environment that has computer systems. And yes, the attribution to Russia compromising the DNC is very solid based on private sector data with government validation. But, to make claims about attacks and attempt to quantify it you actually have to present real data and where that data is coming from and how it was collected. To make claims of new ransomware targeting industrial networks you have to actually provide evidence not simply make a series of analytical leaps. To start making claims of attribution to a state such as Russia just because some poorly constructed indicators alerted on a single laptop is dangerous.

Or more simply put: be careful of analytical leaps especially when they are made without presenting any evidence leading into them. Hypotheses and analysis requires evidence else it is simply speculation. We have enough speculation already in the industrial industry and more will only lead to increasingly dangerous or embarrassing scenarios such as a US governor and senator condemning Russia for hacking the electric grid and scaring the public in the process when we simply do not have many facts about the situation yet.