There’s been two cases recently of industrial control system (ICS) security firms identifying vulnerabilities and also creating proof of concept (POC) malware for those vulnerabilities. This has bothered me and I want to explore the topic in this blog post; I do not pretend there is a right or wrong answer here but I recognize by even writing the post I am passing judgement on the actions and I’m ok with that. I don’t agree with the actions and in the interest of a more public discussion below is my rationale.

Background:

At the beginning of April 2017 CRITIFENCE an ICS security firm published an article on Security Affairs titled “ClearEnergy ransomware aim to destroy process automation logics in critical infrastructure, SCADA, and industrial control systems.” There’s a good overview of the story here that details how it ended up being a media stunt to highlight vulnerabilities the company found. The TL;DR version of the story is that the firm wanted to highlight the vulnerabilities they found in some Schneider Electric equipment that they dubbed ClearEnergy so they built their own POC malware for it that they also dubbed ClearEnergy. But they published an article on it leaving out the fact that it was POC malware. Or in other words, they led people to believe that this was in-the-wild (real and impacting organizations) malware. I don’t feel there was any malice by the company, as soon as the article was published I reached out to the CTO of CRITIFENCE and he was very polite and responded that he’d edit the article quickly. I wanted to write a blog calling out the behavior and what I didn’t like about it as a learning moment for everyone but the CTO was so professional and quick in his response that I decided against it. However, after seeing a second instance of this type of activity I decided a blog post was in order for a larger community discussion.

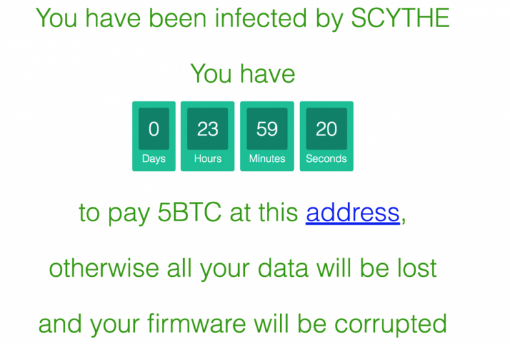

On April 27th, 2017 Security Week published an article titled “New SCADA Flaws Allow Ransomware, Other Attacks” based on a presentation by ICS security firm Applied Risk at SecurityWeek’s 2017 Signapore ICS Cyber Security Conference. The talk, and the article, highlighted ICS ransomware that the firm dubbed “Scythe” that targets “SCADA devices.” Applied Risk noted that the attack can take advantage of a firmware validation bypass vulnerability and lock out folks’ ability to update to new firmware. The firm did acknowledge in their presentation though and in the article that this too was POC malware.

Figure: Image from Applied Risk’s POC Malware

Why None of this is Good (In My Opinion):

In my opinion both of these firms have been irresponsible in a couple of ways.

First, CRITIFENCE obviously messed up by not telling anyone that ClearEnergy was POC malware. In an effort to promote their discovery of vulnerabilities they were quick to write an article and publish it and that absolutely contributed to hype and fear. Hype around these types of issues ultimately leads to the ICS community not listening to or trusting the security community (honestly with good reason). However, what CRITIFENCE did do that I liked (besides being responsive which is a major plus) was work through a vulnerability disclosure process that led to proper discussion by the vendor as well as an advisory through the U.S.’ ICS-CERT. In contrast, Applied Risk did not do that so far as I can tell. I do not know what all Applied Risk is doing about the vulnerabilities but they said they contacted the vendors and two of the vendors (according to the SecurityWeek article) acknowledged that the vulnerability is important but difficult to fix. The difference with the Applied Risk vulnerabilities is that the community is left unaware of what devices are impacted, the vendors haven’t been able to address the issues yet, and there are no advisories to the larger community through any appropriate channel. Ultimately, this leaves the ICS community in a very bad spot.

Second, CRITIFENCE and Applied Risk are both making a marketing spectacle out of the vulnerabilities and POC malware. Now, this point is my opinion and not necessarily a larger community best-practice, but I absolutely despise seeing folks name their vulnerabilities or naming POC malware. It comes off as a pure marketing stunt. Vulnerabilities in ICS are not uncommon and there’s good research to be done. Sometimes, the things the infosec community sees as vulnerabilities may have been designed that way on purpose to allow things like firmware updates and password resets for operators who needed to get access to sensitive equipment in time-sensitive scenarios. I’m not saying we can’t do better – but it’s not like the engineering community is stupid (far from it) and highlighting vulnerabilities as marketing stunts can often have unintended consequence including the vendors not wanting to work with researchers or disclose vulnerabilities. There’s no incentive for ICS vendors to work with firms who are going to use issues in their products for marketing for a firm’s security product.

Third, vulnerability disclosure can absolutely have the impact of adversaries learning how to attack devices in ways they did not know previously. I do not advocate for security through obscurity but there is value in following a strict vulnerability disclosure policy even in normal IT environments because this has been an issue for decades. In ICS environments, it can be upwards of 2-3 years for folks to be able to get a patch and apply it after a vulnerability comes out. That is not due to ignorance of the issue or lack of concern for the problem but due to operations constraints in various industries. So in essence, the adversaries get informed about how to do something they previously didn’t know about while system owners can’t accurately address the issues. This makes vulnerability disclosure in the ICS community a very sensitive topic to handle with care. Yelling out to the world “this is the vulnerability and oh by the way here’s exactly how you should leverage it and we even created some fake malware to highlight the value to you as an attacker and what you can gain” is just levels of ridiculousness. It’s why you’ll never see my firm Dragos or myself or anyone on my team finding and disclosing new vulnerabilities in ICS devices to the public. If we ever find anything it’ll only be worked through the appropriate channels and quietly distributed to the right people – not in media sites and conference presentations. I’m not a huge fan of disclosing vulnerabilities at conferences and in media in general but I do want to acknowledge that it can be done correctly and I have seen a few firms (Talos, DigitalBond, and IOActive come to mind) do it very well. As an example, Eireann Leverett and Colin Cassidy found vulnerabilities in industrial Ethernet switches and worked closely with the vendors to address them. After working through a very intensive process they wanted to do a series of conference presentations about them to highlight the issues. They invited me to take part to show what could be done from a defense perspective. So I stayed out of the “here’s the vulnerabilities” and instead focused on “these exists so what can defenders do besides just patch.” I took part in that research because the work was so important and Eireann and Colin were so professional in how they went about it. It was a thrill to use the entire process as a learning opportunity to the larger community. Highlighting vulnerabilities and creating POC malware for something that doesn’t even have an advisory or where the vendor hasn’t made patches yet just isn’t appropriate.

Closing Thoughts:

There is a lot of research to be done into ICS and how to address the vulnerabilities that these devices have. Vendors must get better at following best-practices for developing new equipment, software, and networking protocols. And there are good case-studies of what to do and how to carry yourself in the ICS security researcher community (Adam Crain and Chris Sistrunk’s research into DNP3 and all the things that it led to is a fantastic example of doing things correctly to address serious issues). But the focus on turning vulnerabilities into marketing material, discussing vulnerabilities in media and at conferences before vendors have addressed them and before the community can get an advisory through proper channels, and creating/marketing POC malware to draw attention to your vulnerabilities is simply, in my opinion, irresponsible.

Try these practices instead:

- Disclose vulnerabilities to the impacted vendors and work with them to address them

- If they decide that they will not address the issue or do not see the problem talk to impacted asset owners/operators to ensure what you see as a vulnerability is an issue that will introduce risk to the community and use appropriate channels such as the ICS-CERT to push the vendor or develop defensive/detection signatures and bring it to the community’s attention; sometimes you’re left without a lot of options but make sure you’ve exhausted the good options first

- After the advisory is available (for some time you feel comfortable with) if you or your firm would like to highlight the vulnerabilities at a conference or in the media that’s your choice

- I would encourage focusing the discussion on what people can do besides just patch such as how to detect attacks that might leverage the vulnerabilities

- Avoid naming your vulnerabilities, there’s already a whole official process for cataloging vulnerabilities

- (In my opinion) do not make POC malware showing adversaries what they can do and why they should do it (the argument “the adversaries already know” is wrong in most cases)

- If you decide to make POC malware anyway at least avoid naming it and marketing it (comes off as an extremely dirty marketing approach)

- Avoid hyping up the impact (talking about power grids coming down and terrorist attacks in the same article is just a ridiculous attempt to illicit fear and attention)

In my experience, ICS vendors are difficult to work with at times because they have other priorities too but they care and want to do the right thing. If you are persistent you can move the community forward. But the vendors of the equipment are not the enemy and they will absolutely blacklist researchers, firms, and entire groups of folks for doing things that are adverse to their business instead of working with them. Research is important, and if you want to go down the route of researching and disclosing vulnerabilities there’s value there and proper ways to do it. If you’re interested in vulnerability disclosure best practices in the larger community check out Katie Moussouris who is a leading authority on bug bounty and vulnerability disclosure programs. But please, stop naming your vulnerabilities, building marketing campaigns around them, and creating fake malware because you don’t think you’re getting enough attention already.