For a few years now I’ve spent some energy focusing on calling out hyped up stories of threats to critical infrastructure and dispelling false stories about cyber attacks. There have been a lot of reasons for this including trying to make sure that the investments we make in the community go against real threats and not fake ones. This helps ensure we identify the best solutions for our problems. One of the chief reasons though is that as an educator both as an Adjunct Lecturer in the graduate program at Utica College and as a Certified Instructor at the SANS Institute I have found the effects of false stories to be far reaching. Ideally, most hype will never make it into serious policy or security debates (unfortunately some does though). But it does miseducate many individuals entering this field. It hampers their learning when their goals are often just to grow themselves and help others – and I take offense to that. In this blog I want to focus on a new article that came out on the blog at the Huffington Post titled “The Growing Threat of Cyber-Attacks on Critical Infrastructure” by Daniel Wagner, CEO of Country Risk Solutions. I don’t want to focus on deriding the story though and instead use the story to highlight a number of informal logical fallacies. Being critical of information presented as facts without supporting evidence is a critical skill for anyone in this field. Using case-studies such as this are exceptionally important to help educate on what to be careful to avoid.

Misinformation

Mr. Wagner’s article starts off simply enough with the premise that cyber attacks are often unreported or under-reported leading the public to not fully appreciating the scope of the threat. I believe this to be very true and a keen observation. However, the article then uses a series of case studies each with factual errors as well as conjecture stated as facts. Before examining the fallacies let’s look at one of the first claims which pertains to the cyber attack on the Ukrainian power grid in December of 2015:

“It now seems clear, given the degree of sophistication of the intrusion, that the attackers could have rendered the system permanently inoperable.”

It is true that the attackers showed sophistication in their coordination and ability to carry out a well-planned operation. A full report on the attacker methodology can be found here. However, there is no proof that the attackers could have rendered that portion of the power grid permanently inoperable. In the two cases where an intentional cyber attack caused physical damage to the systems involved, the German steel works attack and the Stuxnet attack on Natanz, both systems were recoverable. This type of physical damage is definitely concerning but the attackers did not display the sophistication to achieve that type of attack and even if they had there is no evidence to show that the system would be permanently inoperable. It is an improbable scenario and would need serious proof to support that claim.

Informal Logical Fallacies

The next claim though is the most egregious and contains a number of informal logical fallacies that we can use as educational material.

“The Ukraine example was hardly the first cyber-attack on a SCADA system. Perhaps the best known previous example occurred in 2003, though at the time it was publicly attributed to a downed power line, rather than a cyber-attack (the U.S. government had decided that the ‘public’ was not yet prepared to learn about such cyber-attacks). The Northeast (U.S.) blackout that year caused 11 deaths and an estimated $6 billion in economic damages, having disrupted power over a wide area for at least two days. Never before (or since) had a ‘downed power line’ apparently resulted in such a devastating impact.”

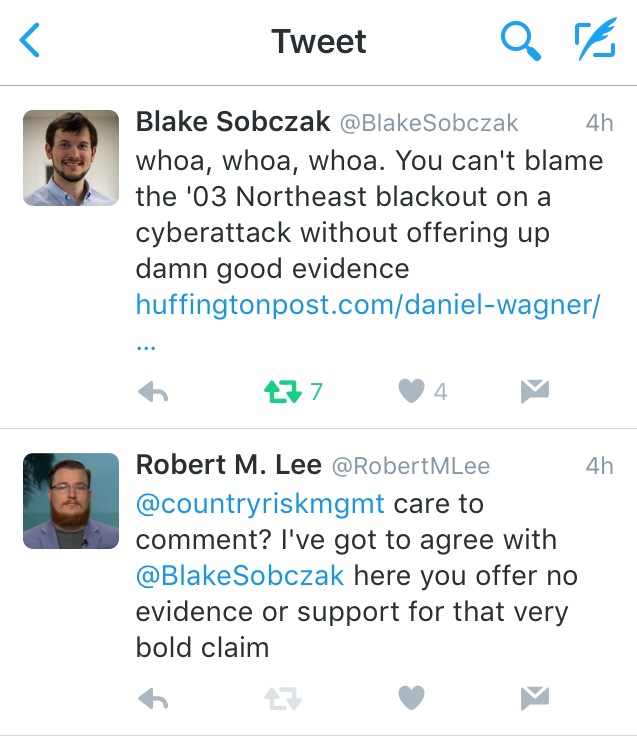

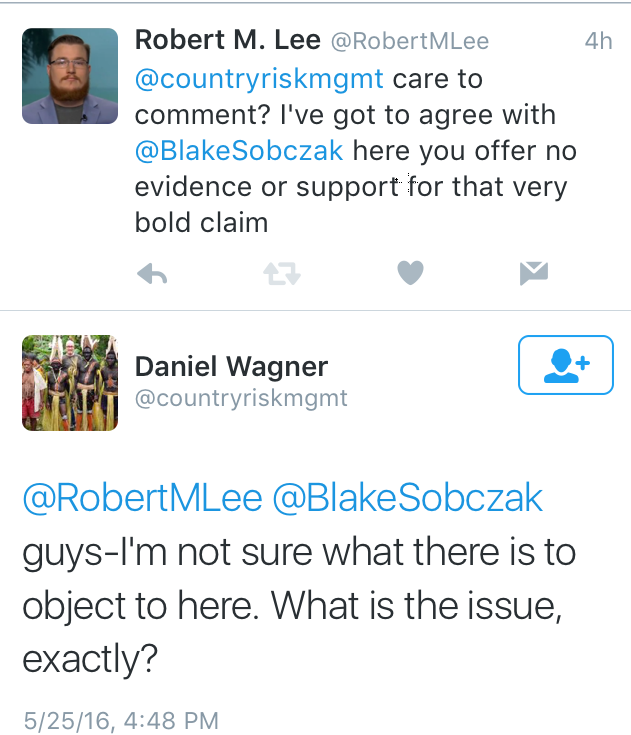

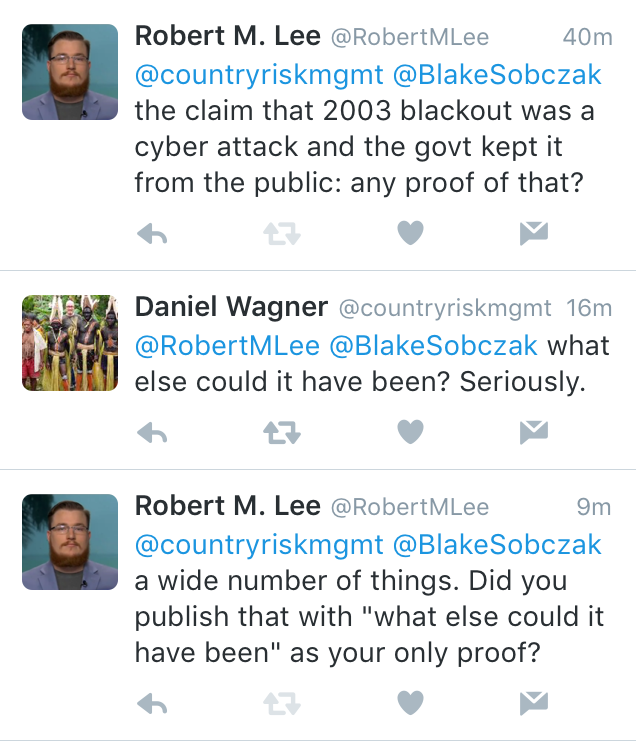

This claim led to EENews reporter Black Sobczak to call out the article on Twitter which brought it to my attention. I questioned the author (more on that below) but first let’s dissect this claim as there are multiple fallacies here.

First, the author claims that the 2003 blackout was caused by a cyber attack. This is contrary to what is known currently about the outage and is contrary to the official findings of the investigators which may be read here. What Daniel Wagner has done here is a great example of Onus probandi also known as “burden of proof” fallacy. The type of claim that is made is most certainly not common knowledge and is contrary to what is known about the event. So the claimer should provide proof. Yet, the author does not which puts the burden of finding the proof on the reader and more specifically anyone who would disagree with the claim including the authors of the official investigation report.

Second, Daniel Wagner states that the U.S. government knew the truth of the attack and decided that the public was not ready to learn about such attacks. He states this as a fact again without proof but there’s another type of fallacy that can apply here called the historian’s fallacy. In essence, Mr. Wagner obviously believes that a cyber attack was responsible for the 2003 blackouts. Therefore, it is absurd to him that the government would not also know and therefore the only reasonable conclusion is that they hid it from the public. Even if Mr. Wagner was correct in his assessment, which he is not, he is applying his perspective and understanding today on the decision makers of the past. Or more simply stated, his is using what information he believes he has now and is judging the government’s decision on that information which they likely did not have at the time.

Third, the next claim is a type of red herring fallacy known as the straw man fallacy where an argument is misrepresented to make it easier to argue against. Mr. Wagner puts in quotes that a downed powerline was responsible for the outage and notes that a downed line has never been the reason for such an impact before or since. The findings of the investigation into the blackouts did not conclude that the outages occurred simply due to a downed power line though. The investigators put forth numerous findings which fell into four broad categories: inadequate system understanding, inadequate situational awareness, inadequate tree trimming, and inadequate diagnostic support amongst interconnected partners. Although trees were technically involved in one element it was a single variable in a complex scenario and mismanagement of a difficult situation. In addition, the ‘downed power lines’ mentioned were high energy transmission lines far more important than implied in the argument.

Mr. Wagner went on to use some other fallacies such as the informal fallacy of false authority when he cited, incorrectly by the way, Dell’s 2015 Annual Security Report. He cited the report to state that cyber attacks against supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) systems doubled to more than 160,000 attacks in 2014. When this statistic came out it was immediately questioned. Although Dell is a good company with many areas of expertise its expertise and insight into SCADA networks was called into question. Just because an authority is expert in one field such as IT security does not mean they are an expert in a different field such as SCADA security. There have only been a handful of known cyber attacks against critical infrastructure. The rest of the cases are often mislabeled as cyber attacks and are in the hundreds or thousands – not hundreds of thousands. Examples of realistic metrics are provided by more authoritative sources such as the ICS-CERT here.

Beyond his article though there was an interesting exchange on Twitter which I will paste below.

In the exchange we can see that Mr. Wagner makes the argument “what else could it have been? Seriously”. This is simultaneously a burden of proof fallacy requiring Blake or myself to provide evidence disproving his theory as well as an argument from personal incredulity. An argument from personal incredulity is a type of informal fallacy where a person cannot imagine how a scenario or statement could be true and therefore believes it must be false. Mr. Wagner took my request for proof of his claim as absurd because he believed that there was no other rational explanation for the blackouts other than a cyber attack.

I would link to the tweets directly but after my last question requesting proof Mr. Wagner blocked Blake and me.

Conclusion

Daniel Wagner is not the only person to write using informal fallacies. We all do it. The trick is to identify it and try to avoid it. I did not feel my request for proof ended up being a fruitful exchange with the author but that does not make Mr. Wagner a bad person. Everyone has bad days. It’s also entirely his right not to continue our discussion. The most important thing here though is to understand that there are a lot of baseless claims that make it into mainstream media that misinform the discussion on topics such as SCADA and critical infrastructure security. Unsurprisingly they often come from individuals without any experience in the field to which they are writing about. It is important to try to identify these claims and learn from them. One effective method is to look for fallacies and inconsistencies. Of course, always be careful to not be so focused on identifying fallacies that you dismiss the claim too hastily. That would be a great example of an argument from fallacy, also known as the fallacy fallacy, where you analyze an argument and because it contains a fallacy you conclude it must be false. Mr. Wagner’s claims are not false because of how they were presented. The claims were not worth considering because of the lack of evidence, the fallacies just helped draw attention to that.